Berna Anat has made it her mission to help young BIPOC take control

of their finances. Through her podcast and social media, she has

been making complex financial concepts accessible and

understandable. Anat's new book, Money Out Loud, continues

this undertaking by covering personal finance topics like budgeting,

saving, and investing. Anat talks with us about her own experiences

with money, how capitalism perpetuates financial illiteracy, and how

to find balance with money.

Please tell us a little about

yourself.

Please tell us a little about

yourself.

I’m a Filipina-American daughter of immigrants, born and raised in

the Bay Area. I’m an author, content creator, speaker, podcast host,

rich auntie in training and Financial Hype Woman. That’s my made-up

way of saying I create financial education media on the Internets,

specifically for young BIPOC. I’m also a double Scorpio, a former

Tahitian dancer, and if you’re gonna ask me “Have I seen (insert

movie or TV show),” the answer is probably no, because I spend a lot

of time in my bean bag, reading.

How was the topic of money treated in your family growing

up and how do you think that affected you?

Money was straight-up not a topic in my family. There’s a study from

the University of Cambridge that says we solidify our understanding

of money between the ages of 7 and 9. The only thing I was learning

about money at that age was the constant confusion between “We have

rice at home,” — a.k.a. we’re broke — and watching my family members

fight over the bill and buy things I knew we couldn’t afford, a.k.a.

we’re… not broke?

One of my core memories about money happened around the 2008 housing

crisis when my family, like so many others, were scammed by

sub-prime mortgages and had to file for bankruptcy. The silent

tension, the refusal to address anything, that quiet, sinking,

shameful feeling. For me, that added up to Adult Berna being

terrified of money, deeply ashamed of my $50,000 of debt, completely

unorganized, and yet having no boundaries when it came to spending

money on my family and friends.

Your book Money

Out Loud is considered a young adult title, but it includes

a lot of information that many adults don’t know. Why do you think

it is that people don't learn enough about personal finances

before they have to actually deal with such matters?

Your book Money

Out Loud is considered a young adult title, but it includes

a lot of information that many adults don’t know. Why do you think

it is that people don't learn enough about personal finances

before they have to actually deal with such matters?

There are a few things that every American has in common, and one of

them? We were born into capitalism — a crappy game with crappy

rules. Really, capitalism only has one rule: Money is power. And

capitalism also depends on keeping certain folks (cough marginalized

communities) disempowered.

I believe the fact that none of us learn about money in school is

incredibly intentional: Capitalism needs busy workers. It doesn’t

need us poking holes and asking questions. Why would a system that

depends on our ignorance want us to understand how money works?

Where would US banks get their literal trillions in overdraft fees

each year if we all understood how banks worked? How would lenders

make money off of our interest fees if we all understood how to

avoid or pay down debt?

We learn nothing about money in school, so we get context clues in

our homes and our communities, where we find a whole lotta silence,

ignorance, and shame. It’s the crappiest environment to try to learn

an already difficult thing.

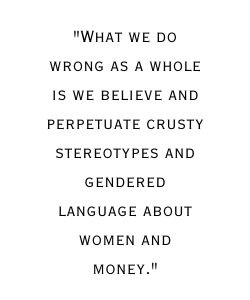

What is one thing you find women do wrong when it comes to

money?

I’d say the one thing people do wrong is believe that women are

“worse” at money than men. A study from the investment app Stash

found that on average, during the peak of the pandemic, men were 17%

more likely to freak out and “panic sell” their investments, whereas

women were 63% more likely to hold tight and even increase their

investments. A 2019 CNBC survey found that men are just as likely as

women to spend on impulse buys, even spending slightly more per

purchase. And it’s not entirely our fault that we ~think~ women are

bad at money — Starling Bank studied 300 magazine articles and found

that 65% of the women & money articles characterized women as

excessive spenders, whereas 70% of the men & money articles

emphasized making more money.

What we do wrong as a whole is we believe and perpetuate crusty

stereotypes and gendered language about women and money. These

viewpoints affect our salaries, the jobs we’re hired for, the way

we’re treated in workspaces, especially in finance. Unhinged

misogynistic vibes.

Some people are spendthrifts and some are penny pinchers. How can

you make sure you have balance when it comes to money?

One important thing is, if you identify yourself as a spendthrift or

a penny pincher, take a second and (compassionately!) ask yourself

how you came to be this way. In Chapter 1 of my book, we do a little

soft dive into unpacking our financial histories. It’s harmful to

shame ourselves for being a certain way with money — you weren’t

born with “bad saver” in your blood. We gotta ask ourselves, who

taught me this? Where did I learn this? How was money treated in my

household? What core money memories affected the way I look at money

now?

We can start to empathize with our money brains, and the money

brains of those who raised us, and we can start to identify what

triggers our spend-thrift or penny-pinching instincts. For example,

my budget has always gone out the window when it comes to going out

with family — a habit I picked up from my mom, for sure. Knowing

this, and reframing it as, “I want enough money to spoil my family

from time to time,” I created a section in my budget specifically

for Spoiling My Loved Ones. That section in my budget gets refilled

once a month, and it’s separate from my rent or bills money, so I

can spend it guilt-free.

Looking back, what was the best and worst thing you did

financially?

The worst thing I ever did financially was open up that friggin’

Bank of America credit card when I was 19, because they were on my

college campus offering a cute sweater at sign-up. I had no business

having a $2,000 spending limit when I could barely manage my tiny

work-study paychecks. But what the hell did I know?! That type of

recruitment targeted folks like me. Cut to me a few years later with

$12,000 of credit card debt and no clue how I got there or how to

fix it.

But — probably hardcore confirmation bias here — the best thing I

ever did financially was share my debt journey with folks on

Instagram for the first time. Yes, it all added up to the career I

have now, but more importantly, it helped me shatter the belief that

money should be a thing we do in secret, that we gotta nurse our

shame individually. Sharing my struggles helped me learn faster from

my community, spark conversation, inspire others to do the same — to

be honest, it made me smarter, made my relationships deepen, and

made paying off debt feel like a whole-a$$ community effort.

Is there a favorite childhood memory that shaped who you

are today?

Whew! Big question! I vividly remember getting my first paycheck. I

was around 12 years old, and I was doing competitive Tahitian and

Hawaiian dancing, like so many other Filipino kids in the Bay Area.

Our group got paid to dance at a restaurant in San Francisco, and

the next week in class, our teacher handed each of us a paper check.

I have no idea how much it was, but I do know that my mom let me

spend the entire damn thing on a PC game where you could design

clothes for Barbies, print them out and color them. The idea that

you could earn money doing something you love, something you’d do

for free anyway, was wild to me. Turns out I didn’t have the chops

to become a professional dancer, but I think that “get paid to be

yourself” bug bit me pretty early.