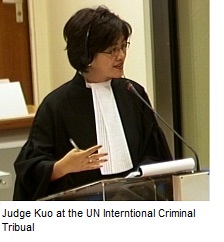

Judge

Peggy Kuo has had many firsts. She was the first in her family to

graduate from Yale and Harvard Law; the first to successfully

prosecute sexual violence as a crime against humanity; and one of

the first Taiwanese-American judges. She began her career as an

Assistant U.S. Attorney in the District of Columbia before

investigating and prosecuting hate crimes and police misconduct at

the Department of Justice as a trial attorney. She then spent 1998

to 2002 at the United Nations

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in

The Hague, which, for the first time, ruled that rape was a crime

against humanity. Kuo returned to New York as litigation counsel at

WilmerHale LLP, presided

over hearings of federal securities laws violations at the New

York Stock Exchange, and was Deputy Commissioner and General

Counsel of the nation’s largest municipal tribunal, the New

York City Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings.

Judge

Peggy Kuo has had many firsts. She was the first in her family to

graduate from Yale and Harvard Law; the first to successfully

prosecute sexual violence as a crime against humanity; and one of

the first Taiwanese-American judges. She began her career as an

Assistant U.S. Attorney in the District of Columbia before

investigating and prosecuting hate crimes and police misconduct at

the Department of Justice as a trial attorney. She then spent 1998

to 2002 at the United Nations

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in

The Hague, which, for the first time, ruled that rape was a crime

against humanity. Kuo returned to New York as litigation counsel at

WilmerHale LLP, presided

over hearings of federal securities laws violations at the New

York Stock Exchange, and was Deputy Commissioner and General

Counsel of the nation’s largest municipal tribunal, the New

York City Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings.

Now a federal magistrate judge for the Eastern District of New York,

Kuo says she always wanted a life in public service to make a

difference in people’s lives. Kuo’s desire to help people started at

an early age. Her dad, an engineer, left Taiwan for New York in 1964

in search of a better life, leaving behind a pregnant wife and

daughter. Two years later, Kuo met her father for the first time

when they joined him as part of the first wave of immigrants allowed

into this country after the passage of the 1965 Immigration

and Nationality Act.

Growing up in Manhattan's Washington Heights wasn’t easy. “There

were very few Asians,” says Kuo, who learned to speak English at a Head Start program and

recalls her older sister pretending to know Kung-Fu when people

called them “ching chong” and other racist slurs. Kuo’s parents

stressed the importance of education and job security--and all four

Kuo daughters excelled in school. “We were mindful that because we

were seen as foreigners, we had to do better than everybody else.”

Kuo says. “There was never any question about getting straight A’s.”

Aware that Chinese culture tended to value

boys more than girls, the Kuo sisters supported each other. “There

were four of us, so it was like ‘Little Women.’ We had a lot of fun,

but we knew we had responsibilities.” The plan worked. Today,

they’re all doctors and lawyers--and Kuo proudly remembers her

parents by her side at her swearing-in ceremony on January 5, 2016,

a particularly poignant day because her mother died shortly after.

“My mom was always one of my big cheerleaders,” Kuo says. “When I

told her I was appointed, she said, “It's about time they made you a

judge!”

We spoke to Kuo about Asians in the judiciary, Asian hate, and why

we need to hold political leaders accountable.

Were you the first Asian judge

in the Eastern District of New York?

I'm definitely the first Taiwanese-American judge, but there were

other Asian American judges before me: Marilyn

Go, Pamela

Chen and Kiyo

Matsumoto. So, I was the fourth Asian American judge in the

Eastern District of New York. Since then, there have been several

more including Diane

Gujarati, Sanket

Bulsara, and James

Cho.

Were there many Asian judges when you started out?

Were there many Asian judges when you started out?

In 1988, there were no Asian American judges in D.C., where I was

practicing, and no federal judges in New York. In 1993, Marilyn Go

was appointed, and only in 1994 was Denny

Chin appointed as a District Judge in the Southern District of

New York.

Are AAPI still underrepresented in the judiciary?

Representation outside the Eastern District is not great. But it’s

getting better. And there are now AAPI judges in places you wouldn’t

necessarily expect, like Colorado, Texas and Michigan.

How did you end up at Yale?

I wanted to go to Yale because of its emphasis on undergraduate

education and because of its Directed Studies program where you read

original works in Western Civilization freshman year. I applied

early action and got in. My parents’ reaction was, “It’s not too

late to apply to Harvard.” So I promised them I would go to Harvard

for law school. I don’t recommend making those kinds of promises!

But, luckily, I got into Harvard Law School four years later.

How many Asians did you see at Harvard Law and how many of those

were Asian women?

My law class had over 600 students, and there were something like 16

Asian Americans. Of that group, maybe half were women. When I

started at the U.S. Attorney's Office, there was only one other

Asian American woman and people got us mixed up all the time.

How did you end up in The Hague--and eventually make history?

I had been practicing law for 10 years and I’d always been

interested in the Nuremberg

Trials after World War II. When I returned from a German

Chancellor fellowship in Berlin, people knew I was interested

in international criminal law, so when the tribunal formed and they

were looking for lawyers, I was approached about joining.

What impact did your experience in The Hague have

on you personally and professionally?

What impact did your experience in The Hague have

on you personally and professionally?

It was amazing because I worked in an international environment

where my colleagues came from different backgrounds and legal

systems. A group of us are still close friends, and we visit each

other in places like Brazil or Australia. We all learned from each

other. Certain things that we take for granted aren't shared by

other legal systems, and so, in that sense, I appreciate what we

have but also see where there might be room for improvement. It was

also professionally very rewarding to meet people and to learn about

law while working alongside them. During the investigations and

prosecutions, I met survivors of atrocities and was inspired by

their strength and resilience.

How did it feel to change international law by having rape

declared a crime against humanity?

We had to be creative because it wasn't a given that the court would

agree with us that rape could be a crime against humanity as a form

of torture or enslavement. And it wasn't a given that the witnesses

would come and testify. There was no reason for them to trust us.

Getting the evidence presented and showing that it could be done was

important, and we had to figure out how to make that happen. Those

of use working on the case took the responsibility seriously, but we

didn’t necessarily think, “Wow, this is historic.” We were just

trying to do the best we could and get the best outcome.

What worried you most about the trial?

The witnesses could have been intimidated because they were all

scared. We were worried that the judges might draw the legal lines

narrowly. We had to come up with both the legal arguments and have

the facts and the evidence to support them.

Those women were so brave to testify against the military

commanders who raped them. There was even a documentary, I

Came to Testify, about them.

They were the real heroes. Most of them were very young, 15-16 years

old, when the crimes happened. By the time they testified, they were

young women in their 20s who had been displaced from their homes and

in many cases, their families. They had to process what had happened

and have the strength to go back and relive the trauma. They told us

they were afraid of how they might react to seeing the perpetrators

and being in the same room with them. But they were all fantastic

witnesses.

Did you celebrate the verdict?

When the verdict came out, there was a lot of press attention,

saying it was a victory and historic first. But in our minds, it was

not enough. For the victims, it will never be enough. They lost

family members, and to this day they don't know what happened to

them. We moved the needle on justice, but there is still a lot that

has to be done. We did not stop war or sexual violence.

What kinds of hate crimes were you prosecuting at the Department

of Justice?

I prosecuted a cross burning case, where someone tried to drive a

mixed-race couple out of a neighborhood. There were attacks on black

churches, some of which were racially motivated. My colleagues dealt

with far right extremist groups who had attacked and killed Alan

Berg, a Jewish radio talk show personality. Some incidents

were violent, and some were meant to be intimidating. My division

also earlier prosecuted the Vincent

Chin case.

So basically, nothing has changed; the hate crimes back then are

the same as now?

Unfortunately, much remains the same.

Are you surprised by the ongoing level

of Asian hate crimes now?

Are you surprised by the ongoing level

of Asian hate crimes now?

There has always been a strain of anti-Asian sentiment running

through American history, from the exploitation of railroad workers

in the West and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1895, to the internment

of Japanese Americans during World War II. There were massacres and

large-scale acts of violence, especially in the 1800s. Asians will

often get blamed and attacked for larger problems in society.

While there are more Asians in this country now than in the past,

the larger number of hate crimes directed against Asians is

distressing because it doesn't have to be that way. Anti-anything is

not a natural thing. My experience in the Balkans showed me that

they were unfortunate to have political leaders who stoked ethnic

divisions for their advantage. A lot of the witnesses in Bosnia told

us people lived in harmony for many years. I hear echoes of that

when I see what is happening here.

Are you saying political leaders here stoke racism and

hate?

Anti-Asian hatred is not a natural outgrowth of COVID or of any

other circumstances. People need to be mindful of the effect of what

they're saying when they talk about political, economic, and social

issues.

What advice do you have for those who might be making the

situation worse?

People have to start seeing each other at a human level. We're all

human beings, and are in society together. We have to be careful not

to inadvertently create divisions where none exist. And people

should not fall back on old stereotypes. We all have a

responsibility to examine our own biases. We have to step back and

ask ourselves, “Am I contributing to the problem? Is there a way for

me to help?” We should call out racism when we see it and be willing

to step in to help the people who are being targeted. It's very hard

to stand up for yourself in the moment if other people don't step

in. That is how bigger problems start. It has been said that the

only thing necessary for evil to triumph is for good people to do

nothing. One thing I've learned from the Balkans conflict is once

things get out of hand, it’s very hard to stop it. And that is

really scary.

So leaders need to be careful because people take their cues from

them?

Stoking any kind of division is harmful. That’s what happened in the

Balkans and with the genocide

in Rwanda. The hatred was stoked by political leaders through

the media. The leaders were saying, “Go after this particular group

because they're cockroaches. They're not even human.” Add to that,

the mob mentality that can exist with a large number of people, plus

violence and emotions, and it’s a recipe for disaster. Another

lesson that people don't talk about very much is the power of media

and the use of dehumanizing language, which can lead people to do

horrible things to each other.

Is there a point of no return?

People talk about the dogs

of war. Once the dogs of war are unleashed, it’s very hard to

stop. All the little signs of conflict have to be addressed early

on. People often feel very powerless, but every little bit helps;

educating yourself about things, and about people, and treating

people with kindness and dignity. All of those things help.

You once said you felt like you were carrying the hopes of your

parents on your shoulders, as well as the hopes of 23 million

Taiwanese and 2 billion Asians worldwide. That’s one heck of a

burden for a kid to carry.

I agree! But I don’t feel I am carrying that burden alone anymore.

There are many others doing wonderful things, so we all share that

burden. No one has to be all things at all times.

It’s hard trying to please everybody and yourself.

I try to encourage everybody to be the best they can. Girls are

often told they can't do certain things, but boys are also made to

understand that they shouldn't do certain things. People shouldn't

hold themselves back because of artificial ideas of what they can’t

achieve. People should not internalize barriers. I've been told

through the Asian American Bar

Association, for example, that there are not many

Asian-American litigators, and one of the explanations being

explored is that Asians see themselves as not someone who stands up

in court and makes arguments.

Because we’re expected to be weak and submissive?

We’re not supposed to complain. If you’re good, don't be showy about

it, and don't be the best one. Be one of the best. My dad still says

things like, “The highest stalk of wheat gets its head chopped off.”

What advice do you have for young Asians who are just starting

out?

Don't be so hard on yourself. Don’t feel like you have to do

everything. Do what you have to do, and then do what you want to do.

Make sure you have a way to support yourself, but then find ways to

make yourself happy. Pursue things that are satisfying and

fulfilling. Be kind to others and be kind to yourself.

What happens after your current term expires on October 8, 2023?

I hope to do this for a long time. I feel like I’m just getting

started.