Christine

Ha shot to fame in 2012 when she became the first blind winner

of MasterChef

with Gordon

Ramsay. Since then, the 44-year-old has made it her mission to

advocate for women, Asian Americans, and the visually impaired.

Whether it’s through TED

Talks or her recent “NMOSD

Won’t Stop Me” campaign, Ha says she’s using her elevated

platform to empower the disadvantaged and to give them hope. Ha was

a 19-year-old student at the University of Texas at Austin when she

first experienced blurred vision in her right eye. It took doctors

four years to properly diagnose her with neuromyelitis

optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), a rare inflammatory

autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that can lead to

blindness and paralysis.

Christine

Ha shot to fame in 2012 when she became the first blind winner

of MasterChef

with Gordon

Ramsay. Since then, the 44-year-old has made it her mission to

advocate for women, Asian Americans, and the visually impaired.

Whether it’s through TED

Talks or her recent “NMOSD

Won’t Stop Me” campaign, Ha says she’s using her elevated

platform to empower the disadvantaged and to give them hope. Ha was

a 19-year-old student at the University of Texas at Austin when she

first experienced blurred vision in her right eye. It took doctors

four years to properly diagnose her with neuromyelitis

optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), a rare inflammatory

autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that can lead to

blindness and paralysis.

It was the second time that disaster struck for Ha; at 14, she lost

her mother to lung cancer. But somehow Ha persevered. “I had to

figure out a way to live my best life, the way I saw it, regardless

of whatever hand I was dealt with,” she says. While coping with her

vision loss, Ha sought to reconnect with her mother by recreating

her favorite Vietnamese dishes using trial and error, her father’s

help, and assistive technology. Ha’s blog, the

Blind Cook, caught the attention of MasterChef producers--and

the rest is history.

We spoke to Ha, who describes her vision as “looking at a very foggy

mirror after a hot shower,” about inner strength, the importance of

self-advocacy, and why she values Asian culture.

How did winning Master Chef change your life?

I’m naturally an introvert and pretty reserved around people, and

suddenly my life was in public view. That took a long time to adjust

to, but it opened up a lot of opportunities like being able to do

more cooking on television, to write a cookbook, and eventually open

restaurants. The biggest thing is having my voice be a beacon of

hope for a lot of people, whether it be women, people of color,

Asians all over the world, or people with vision impairment and

other disabilities. Giving them hope is the biggest reward of all.

It must have been terrifying when

you were diagnosed with NMOSD at such a young age.

It was pretty scary. My first symptom was optic neuritis, or

inflammation of the optic nerve, and I was in college. At that age,

you don't think about dealing with a serious illness. I went through

bouts of numbness and tingling in my legs, as well. I was initially

misdiagnosed with MS (multiple

sclerosis), and it wasn't until some years later that I was

finally correctly diagnosed.

Did you lose precious time from your misdiagnosis?

I was put on MS therapies, which weren’t working because I had an

incorrect diagnosis. So I was still getting a lot of flare ups and

attacks, and it was taking a toll on my vision. I gradually lost my

vision because my optic nerves just atrophied after so many bouts of

inflammation. It was actually a relief to find out I had NMOSD

because I finally felt like “OK, I think this is correct.”

Do you think you’d still have your vision if you were properly

diagnosed?

If I was correctly diagnosed, and I was put on the right treatment,

and if my doctors would have listened to me when I said, “I feel

another bout of optic neuritis coming, and I need the steroids right

away; I feel like a combination of these things could have prevented

me from losing as much vision as I have.”

Did doctors dismiss some of your concerns because you were so

young at the time?

I’ve had doctors talk down to me and made me feel like my symptoms

weren't validated. I was asked if it was because I’m a woman and a

woman of color. I didn't think it was really a racial thing, but I

definitely think it was an age thing. Because I was so young, I was

probably dismissed for not knowing enough or being too inexperienced

to know my body. Part of it was also perhaps being a woman.

So your message is to stay informed and speak up?

I've learned that it’s really important to be an educated patient,

and it's important to find a support network, whether it's other

patients that have the same disease or a healthcare team that

understands and listens to you--and makes you feel like your

feelings and your thoughts are valid. I felt very passive in my

treatment plan, and I didn't realize how disempowering that felt

until I finally found doctors and nurses who participated more fully

and allowed me to participate more fully in my health care plan.

Is that why you’re such an advocate for NMOSD awareness?

It’s exactly why I like to speak up about this--not

only to raise awareness about NMOSD, but about rare diseases in

general. My experience was so isolating, scary, and frustrating that

I want to prevent another person from going through that same

experience. I want to raise awareness because NMOSD primarily

affects the Asian and African American population, so I'm trying to

help others who were initially misdiagnosed with another disease

like MS. Even broader, I’d like to help minimize the loneliness by

connecting patients with other patients and caregivers with other

caregivers, and giving them the right resources so that they can

make educated decisions about their health care teams and the right

treatment plans. That’s why I partnered with Horizon

on this NMOSD

Won't Stop Me campaign.

It’s exactly why I like to speak up about this--not

only to raise awareness about NMOSD, but about rare diseases in

general. My experience was so isolating, scary, and frustrating that

I want to prevent another person from going through that same

experience. I want to raise awareness because NMOSD primarily

affects the Asian and African American population, so I'm trying to

help others who were initially misdiagnosed with another disease

like MS. Even broader, I’d like to help minimize the loneliness by

connecting patients with other patients and caregivers with other

caregivers, and giving them the right resources so that they can

make educated decisions about their health care teams and the right

treatment plans. That’s why I partnered with Horizon

on this NMOSD

Won't Stop Me campaign.

How did you find the inner strength to handle going blind?

I survived it by taking it day by day, even sometimes hour by hour,

or minute by minute. It was a lot of mental strength and

determination. All of us are a lot more resilient than we think we

are. We don't really know how we’ll survive until we're put to that

test. My mom wasn't around, and I love my dad, but he was a very

typical Asian dad, so I couldn't really talk to him. I have great

friends, but none of them were going through what I was going

through. It’s important to acknowledge that I was down and

depressed. As I got older and had more life experience, I realized

that everything is temporal and time will pass at some point. I was

able to get through it by knowing that eventually there was an

endpoint.

Do you think your resilience comes from hearing your parents

talk about their hardships in Vietnam and how they escaped the

Vietcong?

I do attribute a lot of my personality and perseverance to my

parents. I was taught that life is never easy, and you have to fight

for what you want. It would have been better if my parents sat with

me and let me be in that pain and feel the grief. But a lot of how

they parented was how they were brought up. I didn't understand

their experience because I didn't come here on a ship, and I wasn't

a refugee. Until you’re older, it's hard to empathize and understand

the sacrifices they made.

How did your parents escape Saigon during the last days of the

Vietnam War?

They were courting and had just graduated university, and it was a

few days before the fall of Saigon, so it was late April 1975. My

dad ran to my mom's house to ask her to escape to Vietnam, so

basically he was asking for permission to marry her. So they ran to

the US naval ship at the port and fought their way onto the ship.

They escaped before the official fall of Saigon and were at sea for

a while. Their ship broke down and they eventually made their way to

the Philippines and flew to Guam, where they were in a refugee

camp before they were sponsored by a church in Pennsylvania.

They ended up moving to Pennsylvania, then Chicago, and then to LA

where I was born.

Did you start cooking because you missed your mom’s Vietnamese

dishes?

I missed my mom's food because she never taught me how to cook. But,

when I was in college, I had to figure out a way to feed myself.

After several attempts at cooking, I realized that I enjoyed it.

There was something very zen about chopping things up and cooking

them and then being able to feed my friends and my roommates, too.

That’s what sparked my first love for cooking.

Did you have any formal training as a chef?

No, I’m 100 percent self-taught.

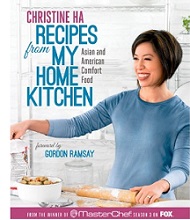

You wrote a cookbook, hosted MasterChef Vietnam, and opened a

few restaurants. What else is going on?

The cookbook was part of winning [MasterChef], so I

wrote it right after and published it the year after. I also did

guest appearances on MasterChef Vietnam and was a full-fledged judge

on season three. I did a lot of guest judging on MasterChef U.S. I

did a cooking show, Four

Senses, in Canada that was geared toward the visually impaired

cook. I did a lot of events and public speaking about what it's like

to be an Asian woman in this industry as someone with a disability.

I’ve also worked with the US Embassy doing culinary diplomacy tours

overseas. Then in 2019, I opened my first restaurant, The

Blind Goat, in Houston.

The cookbook was part of winning [MasterChef], so I

wrote it right after and published it the year after. I also did

guest appearances on MasterChef Vietnam and was a full-fledged judge

on season three. I did a lot of guest judging on MasterChef U.S. I

did a cooking show, Four

Senses, in Canada that was geared toward the visually impaired

cook. I did a lot of events and public speaking about what it's like

to be an Asian woman in this industry as someone with a disability.

I’ve also worked with the US Embassy doing culinary diplomacy tours

overseas. Then in 2019, I opened my first restaurant, The

Blind Goat, in Houston.

Tell us about the Blind Goat and Xin

Chao.

I named my first restaurant the Blind Goat because I’m known as the

blind chef and the goat is my Vietnamese astrological sign. I wanted

to give it a fun name because it's a whimsical modern Vietnamese

restaurant that showcases Vietnamese street food and seafood.

Xin Chao means ‘hello” in Vietnamese. I partnered with Chef

Tony Nguyen. We grew up eating a lot of traditional Vietnamese

food, along with barbecue, Tex Mex, and Gulf Coast cajun food. So I

describe Xin Chao as a contemporary Vietnamese space with

traditional Vietnamese dishes, but with a Texas Gulf Coast twist on

it.

And you just opened Stuffed

Belly.

In June, I opened my third restaurant, called Stuffed Belly, and

this one is a drive thru casual craft sandwich joint with Asian

elements throughout some of the sandwiches. It’s mainly classic

American childhood sandwiches with my fun twist on them.

You have a BA in finance. Why did you switch gears and get an MA

in creative writing?

I was going to take the business route but it was during my

corporate job that I started experiencing all of these NMOSD

symptoms. I had to leave work for a long time because of the attacks

that left me paralyzed from the neck down for a while. I left the

corporate world and started thinking, “What do I really want to do?”

I've always loved to read and rediscovered my love for literature,

so I decided to go back to school and learn the craft of creative

writing.

Is a novel on the horizon?

I've been working on my memoir and I tabled it because of all this

restaurant stuff. But I hope to finish it once these restaurants can

stand on their own.

Do you feel close to your Vietnamese roots?

I identify more as American than Vietnamese because I was born and

raised in America. I think we're taught to be independent thinkers.

And while that's great, I also hold the value of a lot of Asian

thought, where you think about the communal good. But it’s a

balance. It’s important to get along with others and to think

everyone's needs are as important as our own. At the same time, I

value independence and being vocal. I always try to encourage young

Asian girls to find their voice and not be afraid to speak their

minds.

You have three strikes against you--you’re a woman, you're

Asian, and you have a disability. What advice do you have for

those at a disadvantage?

It’s not easy. I have to be two to three times as vocal to be heard.

I grew up as an Asian daughter, so I was always taught to kind of

suck it up; be quiet, be obedient, and just say yes. My mom believed

in some very traditional gender roles, but she was a feminist based

on the things she taught me, like, “Be a strong person and say what

you think.” A lot of my personality comes from her. I understand now

as a business owner that sometimes you have to address things or

it'll just fester. My advice is to be kind and compassionate towards

other people, but don't be afraid to use your voice.