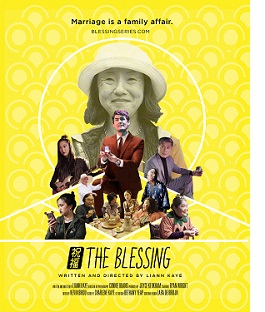

Liann

Kaye gave up her successful day job as a video editor three

years ago to focus on writing and directing. The result? Her

heartwarming and hilarious six-part web series, The Blessing, about the ups and

downs of mixed-race couples, which debuted on YouTube in February in

conjunction with a successful TikTok

campaign.

Liann

Kaye gave up her successful day job as a video editor three

years ago to focus on writing and directing. The result? Her

heartwarming and hilarious six-part web series, The Blessing, about the ups and

downs of mixed-race couples, which debuted on YouTube in February in

conjunction with a successful TikTok

campaign.

Loosely based on Kaye’s own life, each episode follows Leo, a timid

Midwesterner, as he seeks a “blessing” to propose to his girlfriend

from various members of her family. Leo learns something new about

Lana and her Chinese heritage as he meets with her divorced parents,

aunties, grandmother, step dad, and ultimately, the most important

person in Lana’s life, her sister.

Kaye hired a mostly Asian American cast and crew, and shot the first

episode in one, 10-hour day. The Blessing premiered at

festivals nationwide and won “Best Comedy” at the NYC

Short Film Festival, followed by a $20,000 grant from the New

York City Women’s Fund for Media, Music and Theatre to

serialize it.

Born in Hawaii and raised in Scottsdale, AZ, Kaye spent five years

as director of video for Global

Citizen’s international music festivals, where she worked with

Beyoncé, Jay-Z, Coldplay, and Metallica. She most recently signed

with Issa Rae’s management company, ColorCreative,

and is pitching the movie version of The Blessing. What’s

next? Kaye’s first feature screenplay, Electable, about

her student government days, was just attached to Kevin Hart’s Hartbeat

Productions and is being shopped around to streamers.

We spoke to the New York City-based Chinese American director about

her filmmaking journey, the need for more Asian female role models,

and why Asian artists should value their worth.

I appreciate how The

Blessing tackles the complexities of a Chinese-white

relationship with honesty and humor.

I didn’t feel like

people were talking about what it’s really like to be in an

interracial-intercultural relationship and how much communication,

compromise, and sacrifice [is required], especially if it’s with a

white guy. There’s so much to consider, like other people’s

opinions, your own opinions, negotiating privilege and culture, and

getting married. Navigating what traditions to keep or new ones to

make has been a really great journey. It’s been cool to hear from

people who aren't Chinese or American. Someone will say, “I'm

Ethiopian and my husband is Jamaican, and we relate to this

interracial story.” I want people to be able to talk about it and

address the hard things.

I didn’t feel like

people were talking about what it’s really like to be in an

interracial-intercultural relationship and how much communication,

compromise, and sacrifice [is required], especially if it’s with a

white guy. There’s so much to consider, like other people’s

opinions, your own opinions, negotiating privilege and culture, and

getting married. Navigating what traditions to keep or new ones to

make has been a really great journey. It’s been cool to hear from

people who aren't Chinese or American. Someone will say, “I'm

Ethiopian and my husband is Jamaican, and we relate to this

interracial story.” I want people to be able to talk about it and

address the hard things.

I also like that Leo embraces tai chi, durian, and so

many parts of Lana’s Chinese culture. It’s usually the other way

around.

I wanted somebody who had more privilege to demonstrate how to be a

good ally, and how to ask questions, and listen. I faced some push

back, like, "Why is the protagonist a white guy?" I agree that we've

seen so many white male protagonists. However, I felt like I wanted

a blank slate to go into Chinese culture without knowing the inside

baseball of it. Usually, as minorities, we're in white spaces trying

to figure out what the rules are and adapting ourselves, but this

guy, Leo, is in our space.

What did your Asian actors say about their roles?

They said it was really refreshing and exciting to be the dominant

person in the scene; to be the person who gets to intimidate or boss

this guy around. Usually, the power is flipped if you have a white

person and a person of color. They said it was so exciting to be the

one to have the power, like having Leo on his knees when he was

talking with grandma.

Did people actually say they disapproved of Lana dating a

white guy?

There are trolls and people who don't like seeing Asian women date

outside of their own race. I recognize I have a white protagonist in

this series. But, this was my story, and at the end of the day, race

matters. It would be a different story if Leo was a person of a

different race. It takes a lot of courage to be a creative person

putting out work. There are a lot of critics.

How much of the series is autobiographical?

How much of the series is autobiographical?

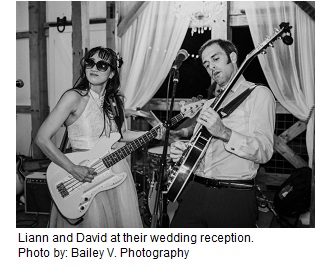

I do have two parents who were born and raised in Singapore and got

divorced. My dad has a girlfriend, and my mom did remarry a white

guy. My husband [audio engineer David

Marchione] did not go around asking every family member’s

blessing to marry me. Leo and my sister did not have tension. I

never got to meet my grandma, but she did have six girls and one

boy. They kept trying for boys, and girls weren’t valued. She raised

the family on her own because her husband left. The [grandma]

episode really resonated with the Asian American community. Many

said, “My grandmother went through this too.”

Was it cathartic for you to share such a personal story with

the public?

The writing process was extremely cathartic. Some things came out of

me that I didn't even expect to address or know was on my mind.

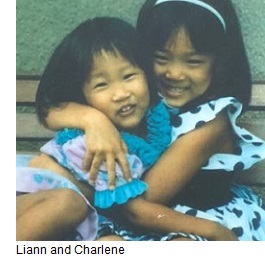

Putting it out was really terrifying. That comes from my sister [Charlene Kaye] being a

musician and me being a music video director for years and never

really saying my own words and exposing myself to the public.

Ninety-nine percent of it has been beautiful, and when I see people

connecting with it, that's totally been worth it. It's been one of

the most beautiful experiences of my life so far.

The first episode, where Leo meets your mom, was so moving

and funny. Why did you take a more serious tone in later episodes?

If we’re going to really address what marriage means to this

character, or all of these people, then you have to talk about the

hard thing: is Leo bending over backwards and killing himself to

prove that he loves this girl enough to be accepted into this

family? This couldn't be done with jokes because it required him to

truly humble himself and really lay himself bare. It’s nice to

address these complex issues with an injection of palatability,

humor, and relatability. Talking about race should be interesting,

fun, and heartbreaking.

Did you purposely write the script with strong female

characters?

I laughed while interviewing a couple of my aunties because they

were like, “Where are these submissive Asian women people are

talking about?” Growing up in America, I was raised to make it a

point to be the opposite of that stereotype. My mom is very strong.

Moving to this country by yourself, and not knowing anybody, and

making it work, is just badass. My sister is very outspoken. The

actress who plays my sister said, “I don't get enough roles like

this where I’m a badass woman."

It’s really nice to see more Asians being cast in film and

TV.

We’re seeing a lot of colorblind casting right now, which is great.

I'm super excited to see more people of color being dropped into

roles, even if it’s largely the best friend or if a girlfriend shows

up and she's Asian.

Do you feel a responsibility to hire more Asians?

We all want to support each other because we've struggled in the

past, and we've been shut out of other film sets and opportunities.

I needed a production designer to decorate the house the way an

immigrant mom would. She knew about ginger jars and waving cats. I

wanted that authenticity. The cast and crew were able to contribute

on set because half of the grandma episode was in Mandarin, so

people listened and helped me with pronunciation. But there's not a

lot of diversity at the executive level. People talk out of both

sides of their mouths, where they want diversity but also need

experience. Most of the minority females that I've worked with are

so good because they work so hard. The issue we need to focus on now

is just speaking up for ourselves because the talent, drive, heart,

and intelligence is already there.

Do you feel like the right time to be an Asian

woman in the arts now?

Do you feel like the right time to be an Asian

woman in the arts now?

Minorities and women are in a very interesting position where the

industry is diversifying. So maybe they’re looking for our stories a

little bit more. But if a writers' room has 10 white men and two

open seats, let’s have a woman or a person of color in there now.

It's not like we're taking anyone's spots because there's still

eight seats for the white guy.

You must be thrilled to see more faces like ours in the

field?

We need to be grateful, but we also need to demand what we want. Be

grateful and know your worth. I’m on Tik Tok talking about Asian

American stuff, but there aren't a ton of us out there being loud,

outspoken, and opinionated. I’m seeing minorities everywhere rise

up. It’s awesome. But I think Asians are still trying to get a seat

at the table. I love Michelle Yeoh’s new movie [Everything,

Everywhere All at Once], and Awkwafina's

and Constance

Wu’s movies. But there are about five A-list AAPI actresses.

And if you don’t get one of them, it’s like, “Is your movie

valuable?” That’s awful.

How do you explain this rise in Asian visibility in the arts

with so much Asian hate right now?

It is so confusing. We're just so polarized. The split is most

visible on Facebook and Tik Tok. They say by 2060, white people will

be the minority. And when the privileged class experiences equality,

it feels like racism because even though they already have eight

seats at the table, we’re taking something away from them. That fear

has been prevalent forever. It very much stems from the fear that

something's going to be taken away.

Charlene told NPR that she wants to be a role model for

Asian American girls because it's difficult to be what you don't

see. Do you feel the same?

Absolutely. I felt the same way when I saw Constance Wu in Hustlers.

She was just beautiful and cool and strong and smart. It made me

feel so proud that I kind of look like her. Seeing her inspires me

to want to make more movies.

You and Charlene are extremely close so it

must have been special to have her music throughout The

Blessing.

You and Charlene are extremely close so it

must have been special to have her music throughout The

Blessing.

Definitely. I’ve been immersed in her music for my entire life. It

was beautiful to be able to put those songs at the end of each

episode and have them be meaningful. It fits with that theme of the

sister being the most important person. The Blessing was a

gift to myself and my husband, and largely to her, too.

Your writing is so good and heartfelt. How did you go from

making music videos to making your own films?

I always identified as a writer. I've always loved writing, and I

took creative writing classes. But true to the Asian American

experience, when your immigrant parents grow up in poverty, you need

to pick a stable job. I just denied that part of myself and, to my

sister's credit, she went off to become a rock star. But then as the

younger one, I had to be the good daughter and hold it down and have

a 401k. I did the right thing until I realized that I was miserable.

I used to tell myself that I don't have any stories to tell; that I

couldn’t write about Asian protagonists. Once it occurred to me that

my experience was very unique and also universal to a bunch of

people who hadn't seen themselves on screen yet, that opened up a

lot of floodgates.

How did you get into screenwriting?

I've always observed people, and I do a lot of homework. I read a

ton of books on screenwriting and got together with people. The

first feature screenplay that I wrote, I just observed the format

and put it together and then submitted it to a bunch of contests and

labs.

It was brave to give up your day job to focus on writing and

directing.

I actually left my job [at Global Citizen] and didn't tell my

parents, with the intent of writing a feature screenplay and winning

the Asian American Sundance fellowship. Even though that did not

happen, I still had a feature screenplay that I kept submitting to

other things. Once I realized it was gonna take a really long time

to make a movie, I made a short film first.

What gave you the courage to leave your job?

Honestly, I think it comes from a panic attack. Like, “I just can't

go on.” I didn't even know what I was going to do, but I knew I had

to stop for a moment. I told myself, “I have enough saved up, so I'm

gonna give myself one year to make this film.” Even though I quit my

job, I still had contacts who hired me for editing. I haven't made a

lot of money on my art yet, but I keep putting it out there.

What was it like releasing The Blessing via the

indie route?

The indie path of producing it and putting it out myself has been

really cool. It was just me spreading the word about it on TikTok

and hustling. The grassroots story has resonated with people. It’s

just a lot of hard work

How do you like being on TikTok?

It can be exhausting to be a public person on the internet--and I'm

not even public--but to be out there and have people listen to you

and hear your thoughts, especially on a platform like TikTok, can be

very draining. But there aren't a lot of outspoken Asian Americans,

so we do need a voice out there to tell our stories.

I was moved by your honesty on TikTok. You said sometimes

you feel insecure and cry.

I definitely don't want to present myself as bulletproof. It’s so

difficult to be a professional woman in this world. You always get

so many different messages. On one hand, you're supposed to be

feminine and sexy and cute, and then on the other side, if you

really want to get ahead, you need to be ballsy and masculine. It

would be so much better if people could be all over the spectrum of

masculinity and femininity. You don’t need to bulldoze and fake it

till you make it. It’s being honest. Sometimes, I feel very

confident and then other times, I’ll feel anxious about putting out

such a personal series and having the world comment on it.

What was your childhood in Arizona like?

I assimilated very well into Scottsdale. I was one of the only Asian

kids. The other Asian kids followed more of a stereotype that I was

terrified of being, so I ran in the other direction and hung out

with a bunch of guys. It took me a long time, even after college, to

realize that a lot of us erased our identity and wanted to be as far

away from our Asianness as possible when we were growing up because

we just wanted to fit in. Now I’m able to embrace it, and this is

what makes me unique and interesting.

How did you and your sister end up in the arts without

artistic parents as role models?

They really resisted us going into creative careers, but I think my

parents, at their core, are both artists who didn't get the

opportunity because of the life that they were born into. During the

Japanese occupation in Singapore, they grew up so poor and worked so

hard to build a stable life for themselves. So they have all this

trauma around money, and having enough, and success, and doing the

responsible thing. But at the same time, as kids, they surrounded us

with a lot of art. There is this artistic side that [my parents]

never gave themselves permission to go after. I hope we can show

them that you can have both.

Interview edited for length and

clarity.